Complex Care Coordination

How can data help community-based models support our most vulnerable patients?

PatientPing was acquired two weeks ago by Appriss! Incredible news for the care coordination space in general but especially meaningful for me because PatientPing is where I spent some of my most formative years learning about healthcare. Launching products there as an early product manager and working directly with providers and patients laid the foundation for the rest of my career in healthcare. Shadowing providers initially for user discovery is what inspired me to consider medicine and ultimately embark this winding journey of becoming a physician-innovator.

One of the most exciting implications of the acquisition is how these combined networks will connect a much wider set of providers in coordinating care for our most vulnerable patient populations. Appriss Health has a near monopoly in software that powers our states’ prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), and PatientPing brings together hospitals, post-acute providers, health plans, and other providers such as Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), social and human service agencies, and behavioral health organizations.

As I consider the populations of patients that need these networks the most, I think about the patients that frequently use city Emergency Departments for social needs that are often just as important as their medical needs - shelter from the elements, their first meal for the week. I think about the justice-involved patient at the homeless medical respite shelter who I helped to obtain his first smartphone and taught him how to call a granddaughter he had never met. I think about the undocumented patients that push off life-saving preventative healthcare services because of the fear that they’d get caught not only without insurance but also without citizenship.

These patients are among the most marginalized in our healthcare system and the very stories that inspired this very newsletter and my own personal north star in medical school. Companies like Appriss/PatientPing help illuminate different parts of these patients’ journeys but there is still much more work to be done both in terms of health policy and data.

Accountable Health Communities (AHC)

The accountable health communities model is an ongoing CMS innovation model that currently supports 29 organizations across the country. They provide funding for infrastructure and staffing needs for community bridge organizations - groups that bridge the gap between clinical care and community services in the healthcare delivery system. As the CMS fact sheet elaborates further, “the model will provide support to community bridge organizations to test promising service delivery approaches aimed at linking beneficiaries with community services that may address their health-related social needs (i.e., housing instability, food insecurity, utility needs, interpersonal violence, and transportation needs)”

The model specifically defines eligibility for navigation services from these community bridge organizations based on the following:

community-dwelling Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries that live in a bridge organization's target geographical area

Having one or more of the five core health-related social needs (Housing instability, Food insecurity, Transportation problems, Utility help needs, Interpersonal safety)

Self-reported having two or more emergency department (ED) visits in the 12 months before screening.

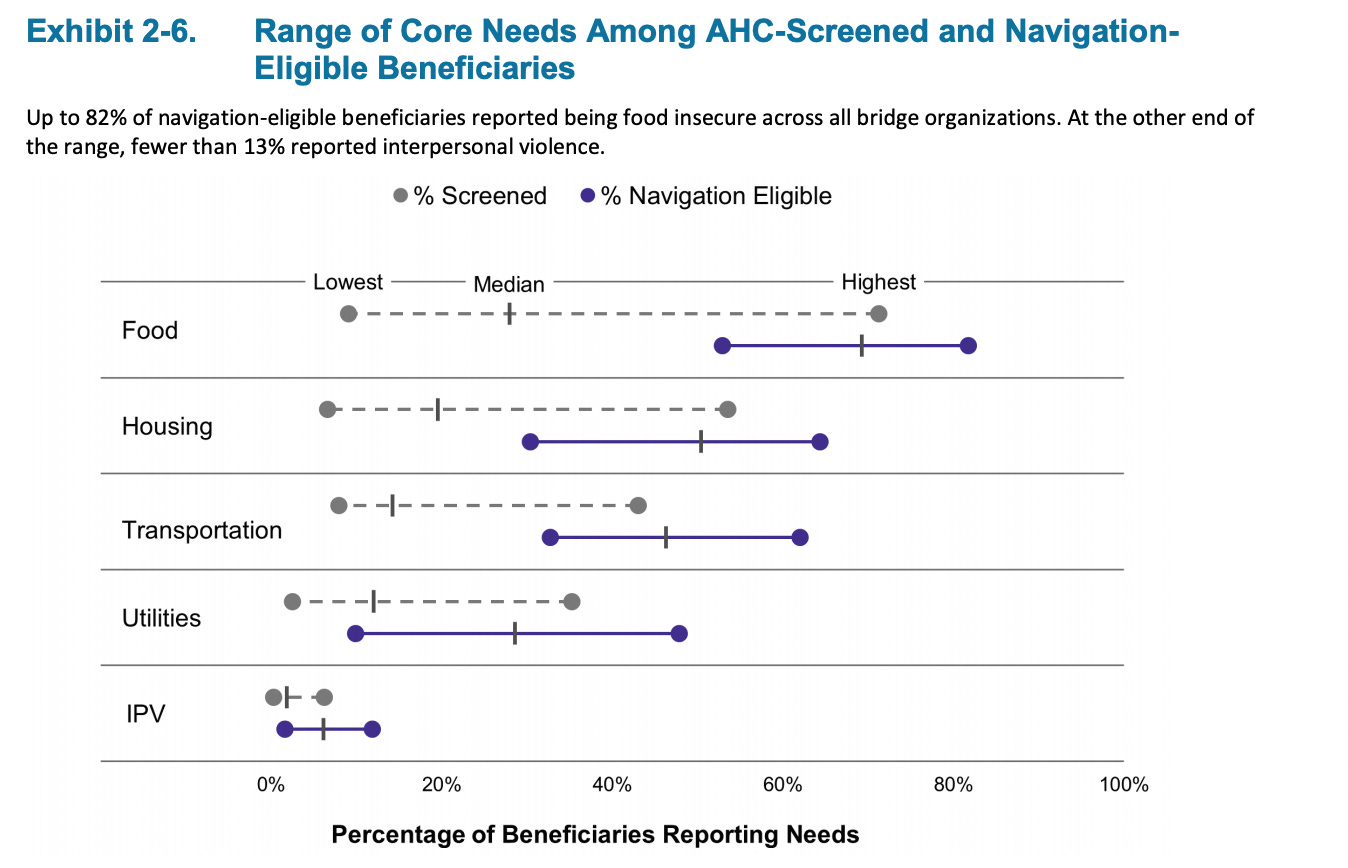

The below graph shows the most pressing needs for AHC-screened and navigation-eligible beneficiary. Food insecurity was the most commonly reported HRSN among navigation-eligible beneficiaries in all bridge organizations except one. The prevalence of food insecurity ranged from 53% to 82% at individual bridge organizations, and the median prevalence across bridge organizations was 69%

Though the evaluation report is only reflecting on the first 2 years of the model, I thought the below takeaways were most interesting from reading through their first evaluation report:

High acceptance of navigation services and some utilization reductions, but evidence at this early evaluation stage indicating that HRSNs were resolved is limited.

74% of eligible beneficiaries accepted navigation, but only 14% of those who completed a full year of navigation had any HRSNs documented as resolved.

Early reductions in ED visits for Navigation-Eligible Medicare FFS beneficiaries are encouraging, but do not yet include Medicaid beneficiaries, who are the majority of those eligible for navigation

Tracking navigation and resolution outcomes was challenging, and improvements are necessary for understanding how and for whom AHC is effective.

Insufficient community resources, especially for housing and transportation, may be a factor undermining the resolution of needs.

Navigation may not be able to demonstrate an effect on health care costs and utilization—not because it is ineffective, but because there may be insufficient community capacity to establish the link between navigation and outcomes.

As important as funding staffing and infrastructure is, Accountable Health Communities would arguably be much more impactful if it also sponsored more lasting and sustainable mechanisms to actually push the ball forward on health equity metrics and HSRN resolution. For example, funding mechanisms or public-private partnerships that allow these communities the meansto stand up a new housing or transportation service for a community if a gap in services is identified.

California has established wellness funds as a mechanism of bringing together private-public stakeholders in locally-governed funds that pool resources to better address community health. This issue brief gives a few examples of how wellness funds can work across stakeholders to align and more efficiently drive interventions for an AHC, but I wanted to highlight their analysis for the different administrative models that a wellness fund can be operated in - balancing flexibility vs speed/cost of implementation.

Health Equity Metrics

All of these important initiatives require accurate and timely data to drive actionable interventions. Similar to the needs of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) that we supported at PatientPing, ACO investment into care navigation services and care coordinators are only moving the needle if they could effectively address the needs of the most needy patient populations at the most relevant time - as Jay Desai reminds us, “rushing to an ER because we have chest pain, starting skilled nursing care after an invasive surgery, or nursing ourselves back to life after a drug overdose.” PatientPing’s work to illuminate these care coordination opportunities through real time notifications (Pings) and relevant (and likely out of network) patient history at the point of care (Stories).

The same opportunities for social care coordination arises for significant changes in a patient’s social determinants of health - the loss of a job, eviction from housing, disability or immobilization of a potential caregiver, etc… Right now there is little to no visibility into these significant life events by our healthcare system. Even if an astute provider or social worker is able to uncover and document these life-altering moments, it can be well after the event and more often than not lost under the pile of unstructured notes. What if we could integrate SDOH data and coordinate changes in social complexity in the same way that we coordinate transitions of care?

Idea: Integrating Eviction Filings to inform Housing as Healthcare Interventions

There are some amazing organizations like The Eviction Lab (founded by Evicted author, Matthew Desmond) that are tapping into local infrastructure to inform and track evictions in real-time. The research working group plugs into esoteric county court systems to create a multi-site, open-source, resource for tracking eviction filings as they happen. What if we could integrate this type of intelligence in real-time into the social service operations of value-oriented healthcare organizations (e.g., Medicaid ACOs, AHCs)? Social workers and housing counselors would be able to work more proactively to address and potentially prevent housing instability. Beyond evictions, more intermediate measures like late rent payments and housing price indices cross-references against family income can be early markers of eventual housing instability.

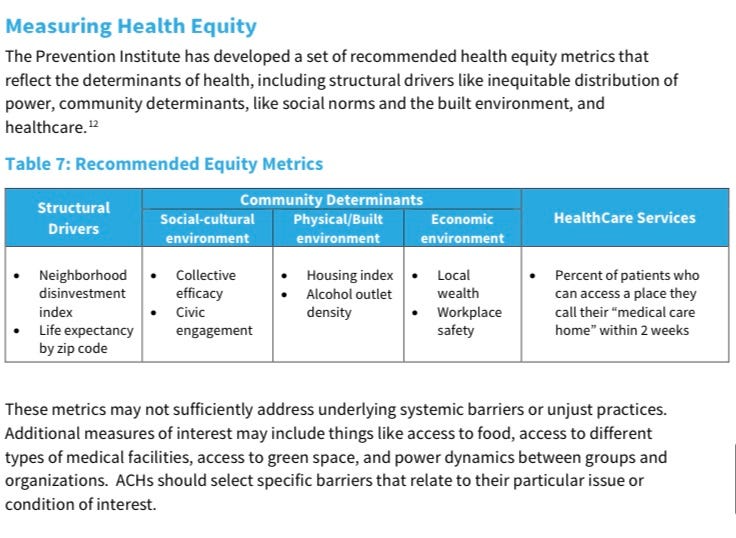

The above data-related guidelines for California Accountable Communities of Health Initiative suggest additional metrics like alcohol outlet density (number of physical locations in which alcoholic beverages are available for purchase either per area) to track longer-term health equity metrics for the community at large. Finding ways to systematically calculate these metrics across communities would add an additional layer into the patient-specific data points above.

All of this work affirms the importance of the type of data and network that companies like Appriss/PatientPing provide in service of illuminating care coordination opportunities. Furthermore, companies like Aunt Bertha, Nowpow, and Unite Us help these models connect with more community-based organizations and close the loop on follow-up and assessing outcomes. However, accountable health communities and similar value-based community health models need data platforms that capture SDOH data not only more proactively, but across a longer timeframe and across an entire community.

Big thanks to Reema Shah for thoughtful comments and edits to this post and a special shout-out to all of the past and current Pingers that have inspired me to embark on this multifaceted career to support marginalized populations in medicine and beyond!