A recent patient anecdote and chat with Dr. Daniel Arteaga inspired this week’s deep-dive into disparities in hospice care. He shared a story of a recent patient who had late-stage peripheral artery disease (PAD) which led to 17 surgeries and bilateral leg amputations. After a painful and prolonged hospitalization, she was discharged to a nursing home but quickly readmitted for multiple infections which would not resolve without additional surgeries. The patient had expressed clearly that she didn’t want to be in the hospital, saying “I feel like you all are experimenting on me” and through her conversations with Dr. Arteaga learned about hospice care - an option that she preferred that could maximize the quality of life and comfort of her remaining days vs. continuing to experience life-extending procedures for her PAD.

The concepts behind Hospice care have been around for centuries - initially tied to religious orders and serving pilgrimages and terminal illnesses like Tuberculosis. Modern hospice care is often attributed to the work of Dame Cicely Saunders, a social worker turned physician who introduced the concept of specialized care for the dying.which focused on the palliation of pain rather than life-prolonging illnesses which may lead to more complications and ultimately may not be aligned with the patient’s goals.of living out their last days in as much comfort as they would like.

My own grandfather went through multiple rounds of chemotherapy and tiring transfusions for multiple myeloma and spent much of his last few months in and out of the hospital - not only a stressful environment for him but also for my father and his siblings as the primary caregivers. Though he had all of his affairs from his will to his advanced care directives, it was clear to me how draining his hospital visits were for him and my family and I wish we had learned more about what palliative care could bring as we were nearing the end of his time.

It turns out that 7 out of 10 Americans say that if given at the choice, they would prefer to die at home. However their preferences don’t line up with their expectations - with only four in 10 thinking they’re most likely to die at home.

When looking at costs and Medicare expenditures, there are also significant savings when you enroll patients in a timely way into hospice care. But despite decreased costs, enhanced quality of life, and potential benefits for both individuals and their families, only half of patients with terminal illnesses end up using hospice care. Much of this discrepancy has to do with both racial and cultural disparities in the way we frame hospice care in the US - let’s take a closer look.

Racial and Cultural Disparities in Hospice Care

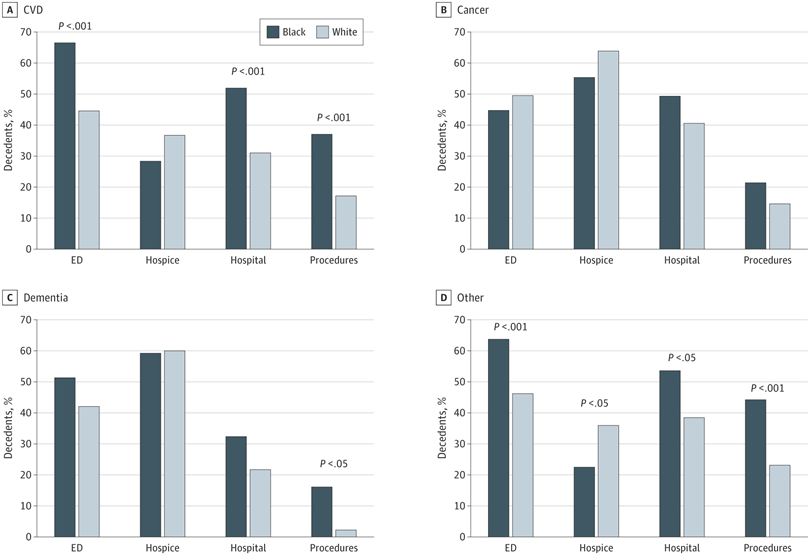

Unsurprisingly, there are significant disparities between Black and white patients which studies like the above have attributed to an increased distrust of the medical system and poor health literacy:

First, other studies have documented that lack of trust in the medical system by Black patients is associated with a reduced willingness to forgo life-sustaining measures and an increased use of the ED for usual care. Second, poor communications between Black patients and health care professionals are documented and may be associated with differences in the intensity of health care service use. In addition, cultural and spiritual differences may play an important in role in choosing to forgo life-sustaining procedures. Black decedents may also have less access to higher-quality end-of-life care, including engagement in advance care planning in part owing to lower health literacy. Source

As the KFF survey also affirms, living as long as possible is most important to Black and Hispanic patients who are also the most critical of the US health care system in preventing death and extending life.

While living as long as possible ranks below other considerations across racial and ethnic groups, blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to say this is “extremely important” to them (45 percent, 28 percent, and 18 percent, respectively). Perhaps relatedly, blacks and Hispanics are also more likely than whites to say the health care system in the U.S. places too little emphasis on preventing death and extending life as long as possible. (Source)

Much of this is cultural and tied to spiritual beliefs as well for many minorities, many of whom value life-prolonging care, full code statuses, and hold beliefs of miracles, God’s will, and/or fatalism. “There’s a lot of African Americans who think saying ‘no’ to medical care is like saying ‘no’ to God. It’s like you are trying to take things in your own hands and not trusting God’s timing” (source) One of the biggest sticking points is around reimbursement policies that require patients to discontinue curative treatment in order to qualify for hospice care. Though some families have found ways to reframe hospice care to align with their values, this choice between treatment vs hospice is a large barrier for many patients who consider hospice care.

This being said, providers themselves are also to blame for end-of-life discrepancies in whose preferences they choose to listen to: “It appears that providers adhered to the EOL (end of life) preferences of white Americans more often than African Americans” (source 1, source 2)

Economics of Hospice Care

In Dr. Arteaga’s words, “For many patients with life-limiting illness, hospice is simply good medicine. But late hospice enrollment (i.e., enrollment in hospice during the last days of life) can be bad business for hospice operators. The upfront costs of hospice enrollment can be greater than the per-patient-per-day reimbursement rates. Hospices become more economically sustainable when patients enroll early and costs are averaged over time.” He added that the many benefits of hospice -- pain and symptom control, anticipatory counseling and additional time with loved ones -- are diminished when hospice referrals are delayed to the eleventh hour.

However, “most individuals who use hospice care are admitted very close to the end of life. Short hospice stays (≤3 days) have increased to 28.4% of all hospice stays, and 14.3% of patients with cancer who enroll in hospice do so in the last 3 days of life.” (source) Medicare covers 6 months of hospice care and renews coverage if your physician certifies that you continue to be terminally ill with a life expectancy of 6 months or less.

Though hospice reimbursement itself doesn’t seem to be the issue it was only as recent as 2016 when Medicare began reimbursing providers for being the conversation around hospice care through reimbursing advance care planning under Part B.

Recently, CMS rolled out a value-based insurance design model specific to hospice benefit which allows Medicare Advantage plans to take complete financial responsibility for all Medicare services, including hospice care, for their members who are in hospice. This has incentivized commercial payers like Humana to develop stronger partnerships with hospice and palliative care providers. Health systems like Mt Sinai are also developing an interest in how to support more community-based palliative care models as in their partnership with Contessa Health, an exciting expansion upon Mt Sinai’s already impactful hospital at home program.

With enough innovation happening in both reimbursement and care delivery of hospice services, my attention is focused on increasing equity related to hospice enrollment and education.

Idea: Culturally-Sensitive Hospice Enrollment

As a follow-up from my post last month on culturally sensitive care navigation, I believe there’s an opportunity to design a more graceful and culturally tailored on-ramp to hospice care. What if we trained end of life counselors who were former caregivers and/or hospice providers to help build trust and competency in local communities?

They would be experts in helping the family navigate many of the challenging conversations around hospice care related to cultural and/or spiritual beliefs about end-of-life care. Regardless of the family’s decision, they would be compensated in a way that didn’t incentivize hospice care if it went against the family’s values - similar to how independent brokers work in the world of Medicare enrollment.

We could partner with hospice providers in streamlining enrollment and also hospital providers, especially those who may have a less robust palliative care service and perhaps no dedicated counselors or social workers who could have these sensitive conversations. Cost-savings derived from bringing more consistent (and persistent) enrollment to hospice providers and also avoiding more unnecessary (and expensive) end of life care for hospital providers, would help sustain our proactive enrollment efforts.

Over time this could evolve into a more full-stack hospice service that provides more of the infrastructure to help health systems develop their own home-based palliative care capabilities, or integrates with companies like Aspire Health.

Idea: Give PCPs (or Oncologists) Skin in the Game

The conversations that precede a referral to hospice are personal, emotional and difficult. Intuitively, the clinicians that know the patient best should be the ones to initiate these delicate conversations. Usually, the primary care doctor (or the oncologist) is best suited to explore these topics and recommend referral to hospice, when medically appropriate and consistent with the patient’s goals of care.

Right now, PCPs carry much of the responsibility of transitioning patients to hospice. They discuss end-of-life preferences and plans, involve palliative care specialists and refer patients to hospice. They do this important work despite the fact that fee-for-service models, if anything, disincentivize referral to hospice. After all, enrollment in hospice often means that the patient no longer receives care from the PCP.

It would be nice to see this contradictory paradigm undone. If referral to hospice can provide so much benefit to patients, we should incentivize physicians to broach these difficult and complex conversations when medically indicated. I can imagine reimbursement models that provide bonus payments to PCPs (or oncologists) whose patients enroll in hospice in a timely manner. These payments should not be so high as to incentivize PCPs to inappropriately “push” hospice onto their patients, but enough to make PCPs think “Is my patient an appropriate candidate for hospice now? How about three months from now?”

Source: The American Society of Clinical Oncology successfully advocated for the addition of this merit-based incentive for eligible clinicians, but we’d argue that these incentives could be applied more broadly beyond cancer for other life-limiting diseases like dementia, end-stage heart disease and kidney failure.

Intuitively, it makes sense that we should be building tools and solutions to facilitate this incredible work by PCPs and Oncologists. But as things currently stand, these physicians have little “skin in the game” (i.e., reimbursement) as it relates to end-of-life conversations and referrals, making them unlikely users/customers for such products. Changing the way we pay for this important work could unlock new demand for novel approaches to the issue of hospice discussion and referral.

Huge thanks to Dr. Daniel Arteaga for our thought-provoking conversation which inspired this post, and his comments and co-authorship throughout. We’d love to learn more from folks working in the hospice space, especially anyone working in enrollment or tech-enabled hospice care delivery models - give us a shout on Twitter @arteagamd or @sk_leung or reply directly here!

If you’re into more deep-dives into ways we can build a more equitable, efficient, and cost-effective healthcare system - subscribe and send in any suggestions for future topics!

This was excellent