Disparities in Palliative Care and Serious Illness Communication

How do we bridge cultural + language gaps in understanding prognosis of serious illnesses?

One of the most striking observations I had during my palliative care rotation was how so many intersecting social factors and layers of disparity play a role in serious illness communication. As part of the palliative care consult team, one of our responsibilities was to organize and lead family meetings where we would guide teams in exploring and discussing goals of care. These conversations would often be when patients and their families would come to grips with the reality of their terminal illnesses and we would ask what is most important to the family moving forwards

Especially when working with non-English speaking patients and patients of color, I saw so many logistical and social hurdles that prevented the most empathetic and effective communication of serious illness: scheduling with family members and care teams, arranging for an interpreter (ideally a live interpreter), baseline health literacy, distrust of the institution of medicine, etc… All of these factors play a role in how patients would understand their prognosis, stage of disease, alternative treatments, hospice care, etc…

To take one poignant example, there was a patient that had been receiving chemotherapy for many years for stage IV lung cancer that had metastasized to the brain. Though the patient had regularly attended chemotherapy sessions for a while, the family didn’t seem to fully understand that the cancer had continued to spread aggressively. As the cancer spread and the prognosis worsened, there was additional misunderstanding of a surgery that was offered as a palliative (aka non-curative) measure to reduce the frequency of seizures and pain felt by the patient. The patient’s wife strongly denied the surgery - feeling like they were misled in fully understanding the poor prognosis of the cancer. As the patient’s healthcare proxy, she felt that it would result in a similar or worse outcome than all the treatments up until this point. She expressed later a fear that their denial actually led to mistreatment of her husband’s motor weakness when she felt that the care team was denying medications (when in fact, the nurse was appropriately waiting for a physician’s order to correct for lab abnormality).

Our team attempted to bridge some of these cultural and language gaps through a family meeting where we clarify the patient’s goals of care and mediate questions about their prognosis and pathways for care. We learned (through an interpreter) that a flight was booked in a few days for the patient to return to their home country so that the patient could live out his final days surrounded by his children and immediate family. Coming out of the meeting, we became his advocates for stabilizing the patient’s seizures as much as possible for this upcoming trip and ensuring as smooth as a discharge as possible.

Reimbursement of Advance Care Planning

At the core of these individual and systemic misunderstandings are more structural issues that cut across the gaps in care and coordination of information. A lot of these gaps derive from the poor reimbursement rates that the hospital receives for “Advance Care Planning” which much of this activity falls under. CMS 99497 and 99498 break down these (usually longitudinal and multifaceted) conversations into 30m increments.

Moreover, the fee-for-service nature of these CPT codes mean that palliative services in most hospitals are not administered in a value-oriented manner, but a volume-oriented one. This structural design stretches consult teams thin and creates missed opportunities to intervene more proactively and longitudinally in cases where palliative care can actually decrease overall healthcare utilization.

There are more value-based payment models that can support more interdisciplinary palliative care measures through Medicare Advantage’s value-based insurance design, Primary Care First, and Direct Contracting which enables primary care physicians to partner directly with palliative physicians to provide more comprehensive and interdisciplinary services across the patient’s care continuum.

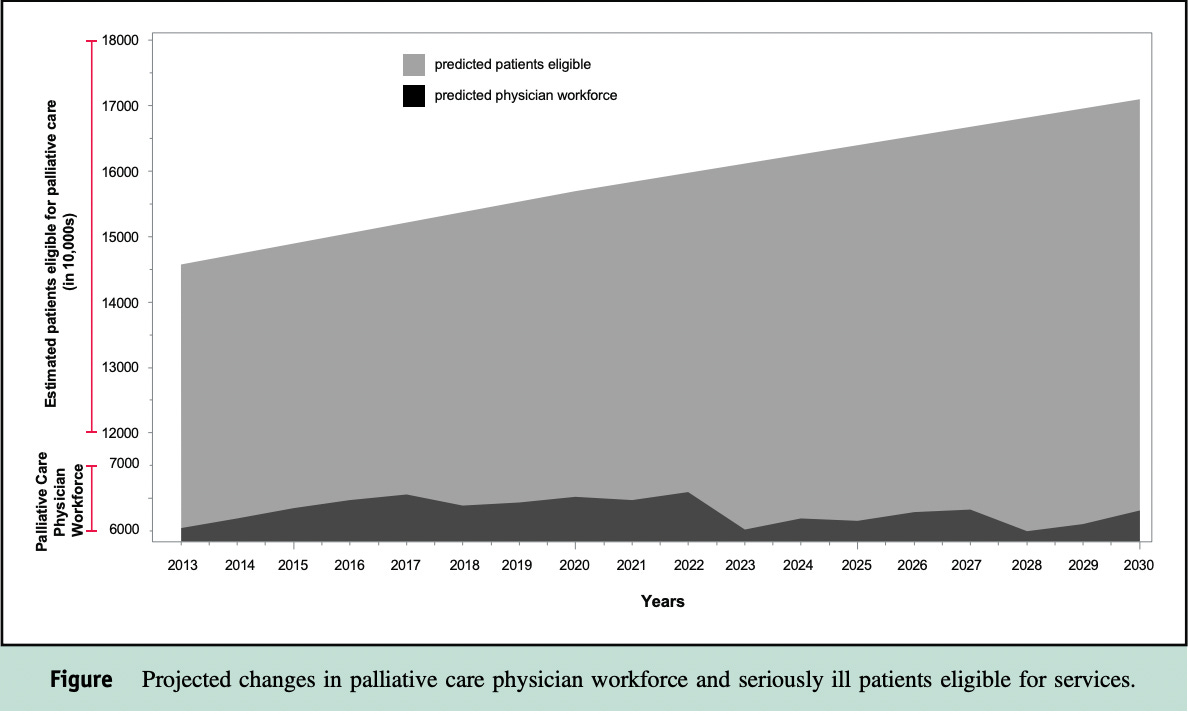

Investing in Professional Workforce Capacity and Primary Palliative Care Education

There’s a growing shortage of palliative care physicians in the US - latest workforce projections estimate a shortage of 18,000 physicians which will only widen with 10000 Americans aging into Medicare every day. In a follow-up survey and report via Health Affairs, Dr. Arif Kamal cites “burnout” as one of the key reasons why palliative care physicians are retiring and recommends passage of the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act to expand Medicare graduate medical education funding for palliative medicine physician fellowships.

Perhaps a more generalized and cost-effective investment would be integrating basic primary palliative care skills to practitioners in all specialties (but particularly emphasizing heme/onc, critical care, etc…) where serious illnesses are seen more frequently. I’m grateful for the opportunity to carry forward the learnings I’ve had on palliative care so early in my clinical training, but imagine that training residents (perhaps in internal medicine) to more comprehensively manage end-of-life care needs can help provide more capacity across the board.

At Mt Sinai, medical students have a required one-week rotation on the palliative care unit, but internal medicine physicians have palliative care only as an optional elective. Thus, the service is staffed mainly supported by fellows from Palliative Medicine or the integrated Geriatrics-Palliative program.

Community-based and Home-based Palliative Care Models

In addition to palliative care programs at academic medical centers, I’m optimistic about similar community-based services scaling in partnership with commercial payers especially in rural and non-urban areas.

There have been a few companies launched in this space (namely Aspire Health which was acquired by Anthem/CareMore) and Mettle Health, launched by palliative care thought leader Dr. BJ Miller. These newer models working outside of a traditional academic health system which provide a more equitable and accessible access to palliative care especially in a community-based setting. Aspire in particular is aligned with a number of CMS value-based initiatives, namely Primary First via the advocacy of C-TAC (Coalition to Transform Advanced Care):

Under Primary Care First, providers would receive upfront payments for treating a focused population of patients with serious illness, aligning closely with C-TAC’s mission to promote value-based, person-centered care. HHS plans to allow providers to apply for the new model by this summer and launch the program in January 2020.

Hospice and long-term home care care have seen some major acquisitions and mergers over the past few years with WellTower and Promedica acquiring SNF giant HCR Manorcare in a joint venture and Humana acquiring Kindred. I’ve seen less tech-enabled service approaches in the hospice space but admire the technology-oriented approaches of Vital Decisions, Iris Healthcare, Cake (end of life planning), Vynca (advance care planning coordination), and in this space which enable providers. I wonder if there is an Aspire Health-like opportunity if MA reimbursement continues to grow in the direction of Humana’s value-based hospice model.

Huge thanks to my preceptors whom I worked with these last two weeks in palliative and geriatric care - Dr. Julia Frydman, Dr. Lauren Kelly, and Dr. Noelle Marie Javier - from whom I’ve been learning a tremendous amount about caring for patients with serious illnesses. Thanks as well to Dr. Dan Arteaga’s thoughtful clinical + digital health-oriented perspective as well. Grateful to be starting my clinical year with such an empathetic specialty and interdisciplinary team which encompasses spiritual and interdisciplinary components in addition to our clinical perspective.

I’d love to hear from you if there are areas of clinical medicine I can keep a closer eye on as I continue on in my clinical rotations - much of this newsletter in the coming months will be how I process individual patient encounters and observed gaps/disparities in care by zooming out and taking a systems-level perspective to what I witness on the floors.